How a Cuban refugee became one of the CIA’s fiercest operatives

In the late 1960s, Enrique “Ric” Prado was a brawler who ran with local street gang the Miami Crowns. But the Cuban refugee also dearly loved his adopted home of the United States — so when anti-war protestors started burning American flags at Miami-Dade Junior College, Prado recruited his crew to fight the demonstrators.

Get a Year of CocaCola along With a Fridge!

Enter your mobile number now for a chance to win.

Click Hare

After the Crowns stormed the campus and physically attacked them, the hippies scattered, the ground littered with broken protest signs and bead necklaces. The campus newspaper ran a piece about Cubans defending the American flag, which made Prado proud.

“That was a watershed moment,” Prado writes in his memoir, “Black Ops: The Life of a CIA Shadow Warrior” (St. Martin’s Press), out now. “Defending our country from people who wanted to tear it down? That stirred something in me.”

Fidel Castro’s communist revolution had chased Prado’s family from Cuba in 1962. They had once led a comfortable, middle-class life in their home country, but when Castro took power, the communists seized the coffee shop his father owned, as well as his grandfather’s gas station and cigar-rolling store. As the country became dangerous — Prado survived his first firefight at 7 — they decided to flee.

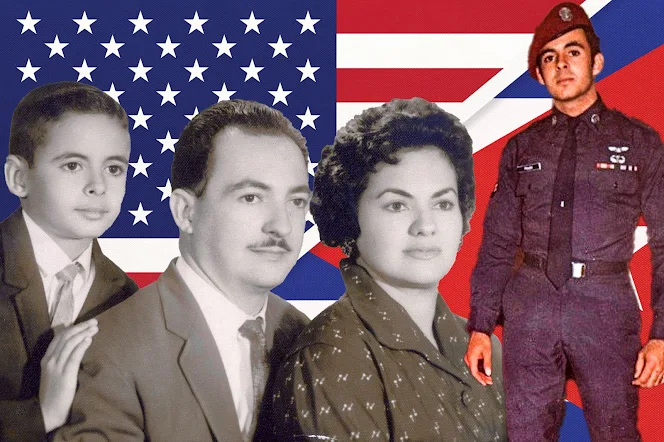

The Prado family before fleeing Cuba. Young toddler Ric Prado stands in the front row center.

The Prado family before fleeing Cuba. Young toddler Ric Prado stands in the front row center.“There was only one place to go: America,” he writes.

Their new life was not easy, and the family struggled, with six people living in a Miami apartment built for two. Through hard work, his father bought a house in Hialeah, a far-flung Miami suburb where many other Cubans fleeing Castro’s revolution would settle down.

The Prados were living the American dream and a family of “ardent patriots” was born.

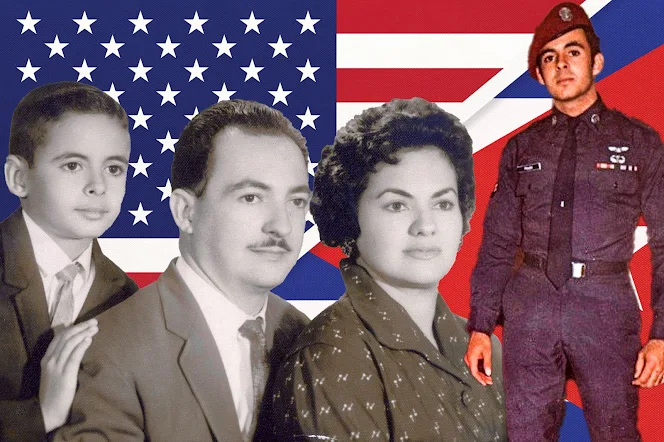

A young Ric Prado in Hialeah, Fla., where his dad worked to move the family from their cramped Miami apartment.

A young Ric Prado in Hialeah, Fla., where his dad worked to move the family from their cramped Miami apartment.Prado was a good student when he first came to the US, but soon his need for excitement — he was a big fan of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels — led him to karate, weight-lifting and petty crime. Life on the streets with the Crowns was more thrilling to him than the classroom. Even so, Prado enrolled at Miami-Dade Junior College and quit his life as a small-time criminal in 1971 when a fellow student told him about his adventures in the US military. Impressed, Prado enlisted in the US Air Force’s Pararescue Jumper team. He was given SCUBA and parachute training, taught survival techniques, and became a fully-certified combat medic.

Sehen Sie sich jetzt Ihren Lieblingssport an!

Geben Sie jetzt Ihre Informationen ein, um loszulegen

Click Hare

After the Air Force, Prado worked for Metro Dade Fire Rescue and joined the National Guard to become a Green Beret. His application for the CIA had been rejected, but the agency called him in 1981, when they needed a Spanish-speaking officer with survival skills and cojones.

In the Reagan years, Ric Prado (clutching rocket launcher) trained the Contras to fight communist Sandinistas as part of the CIA’s “tip of the spear” in Nicaragua.

In the Reagan years, Ric Prado (clutching rocket launcher) trained the Contras to fight communist Sandinistas as part of the CIA’s “tip of the spear” in Nicaragua.Prado was given a temporary CIA assignment to travel to Central America and assist the Contras fighting the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. Prado hated what Castro had done to his native land, so he whole-heartedly joined the Contras in their battle against the communist Sandinistas. “[The Contras’] crusade became my crusade,” he writes.

The clandestine mission was one tentacle of the Reagan Doctrine (which involved defying the Soviet Union around the globe), and Prado delivered food, medical supplies, and ammunition to the impoverished Contras living in jungle camps. He provided mortar training, taught military strategy and offered medical help. He also survived a gun battle with the Sandinistas on his first day in the jungle.

Prado carried all these weapons while fighting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

Prado carried all these weapons while fighting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.“Bullets whined and cracked,” Prado writes. “I unslung my AR-15 and rushed to join the fight.”

For three years Prado was the “tip of the spear” of the CIA’s efforts in the battle for Nicaragua. There, Prado dealt with Argentine military advisers, who had been sent north to help the Contras even before the US got involved. They were a nasty group of soldiers — likely veterans of Argentina’s notorious death squads — who were supposed to assist the Contras but mostly wasted American dollars “drinking and whoring.”

Dinner in one of the Miskito camps, Prado on the right, where living conditions were primitive at best.

Dinner in one of the Miskito camps, Prado on the right, where living conditions were primitive at best.‘I had to pinch myself . . . looking for clandestine landing zones in a hostile desert for my beloved CIA. Hooyah!’

Ric Prado on the thrill of a top-secret op in 2000Within two months of getting to Central America, Prado ended what he saw as “a get-rich-quick scam with Uncle Sam as the mark,” telling those South Americans their days of wasting American money were done.

The senior Argentine officer who outranked Prado couldn’t believe a lowly “US captain” dared speak to him that way, but Prado just smiled, explaining “the important part is the ‘US.’”

When that officer complained to American higher-ups about Prado’s insubordination, he was told “Ric is our guy.” Translated from military-speak, Prado writes, that meant “F–k you” — and after that, the Argentines did what they were told.

In the Air Force’s Pararescue Jumper team, Prado was given SCUBA and parachute training, taught survival techniques, and became a fully-certified combat medic.

In the Air Force’s Pararescue Jumper team, Prado was given SCUBA and parachute training, taught survival techniques, and became a fully-certified combat medic.Later, a group of Contras became displeased with Prado, and a friendly local warned him of an assassination attempt. Prado spent that evening not in the cottage he was offered but alone in the woods, where he watched four rifle-toting soldiers sneak into his residence in a failed attempt to murder him. The next day Prado acted like he didn’t know about the attempt on his life, luring the leaders of the plot onto an American helicopter sent by his US superiors. Prado told the men they were needed back at Contra headquarters and never saw them again, although he later did hear they might’ve been “executed.”

“I was okay with that, especially when the good guys win and a dirtbag gets his due,” Prado writes.

In 2000, Prado led a team into an African city he can’t name but refers to as “Shangri La,” a place where every terrorist organization in the world was known to have a presence.

In 2000, Prado led a team into an African city he can’t name but refers to as “Shangri La,” a place where every terrorist organization in the world was known to have a presence.In early 1984, Prado returned to the CIA’s Operation Course, colloquially known as “the Farm.” There he was taught “tradecraft,” including “dead drops, running agents, covert surveillance and evading enemy tails,” and was hired full-time as a CIA operations officer. That would lead to a quarter-century career of global adventures, offering Prado the chance to “strike back” against anyone who threatened the United States.

In Nicaragua, he organized underwater bombing raids on Sandinista strongholds, blowing up a gas depot at Puerto Cabezas. Also during that mission, Prado was bitten in the face by a Portuguese man-of-war jellyfish, but that didn’t slow him down. “It stung,” he writes dismissively of what could have been a major medical event.

Prado’s awards from a lifetime of service in the CIA from 1980-2004 include the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, the highest medal given to a retiree.

Prado’s awards from a lifetime of service in the CIA from 1980-2004 include the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, the highest medal given to a retiree.In 2000, Prado led a team into an African city he can’t name but refers to as “Shangri La,” a place where every terrorist organization in the world was known to have a presence. On a trip through the desert, the CIA men slept in their cars, waking up to a line of camels walking through a sunrise like a scene from Lawrence of Arabia.

“Again, I had to pinch myself as to my luck: the Cuban-born kid from Hialeah, looking for clandestine landing zones in a hostile desert for my beloved CIA. Hooyah!,” Prado writes.

Over a long career, Prado jumped from a helicopter into the Pacific Ocean in a last-ditch effort to save a Contra attack team whose boat had lost power. He caught North Korean diplomats in an effort to turn them into American spies. He survived assassination attempts in Central America and the Philippines.

Prado’s only regret while working for the CIA? That they didn’t take out Osama bin Laden when he lived in Khartoum, Sudan, in the ’90s. REUTERS

Prado’s only regret while working for the CIA? That they didn’t take out Osama bin Laden when he lived in Khartoum, Sudan, in the ’90s. REUTERSIn the months that followed 9/11, Prado put together a CIA counter-terrorism team with a classified “special capability” to deal with the world-wide fight against al Qaeda. He even presented the idea to Vice President Dick Cheney, who nodded in approval and thanked him for the risks he was willing to take for his country, he writes.

But intra-agency politics came into play, and the plan was ultimately scrapped. Prado’s CIA career was reaching its conclusion, perhaps due to his overzealousness in trying bring the fight to the terrorists of the world.

“It became very clear that I was not welcome in the agency anymore,” he writes.

Now retired, Prado lives in the Southeast with his pup RED (Retired Extremely Dangerous).

Now retired, Prado lives in the Southeast with his pup RED (Retired Extremely Dangerous).Prado retired from the CIA in 2004, but not before being awarded the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, the highest medal given to a retiree. Prado, now 70, keeps at his favorite job — “f–king with the bad guys” — working in private security.

If he has any complaint about the CIA, it’s his belief the agency too frequently pulled its punches.

Working at the CounterTerrorism Center (CTC) in Langley, Va., in 1995, Prado first heard of Osama bin Laden, a notoriously bad actor known to want to kill Americans. At the time, bin Laden was living in Khartoum, Sudan, without much security and attending the same mosque five times daily. Eliminating the man would’ve been a simple task: Prado’s CIA colleague, Billy Waugh, even physically bumped into the terrorist in Khartoum one day as he climbed from his white Mercedes. But the CIA refused to act, as President Ford had signed an Executive Order, banning political assassinations, and President Carter had signed a second prohibiting the agency from even being indirectly involved in such hits.

Prado never understood it, but bin Laden was allowed to live long enough to perpetrate the heinous attacks on 9/11. He would’ve preferred it if the CIA had allowed its officers to act more like Wyatt Earp, who he calls a “skull-splitting bad-guy stomper.”

“It was our nation’s leadership that often failed to measure up,” he writes. “When you have pit bulls ready and willing to go after America’s enemies, only to be chained in the yard by career-obsessed managers, you cannot win a war. It only gets prolonged.”

Post a Comment